Lavish your adoration onto my friends, the rad lady and gender non-conforming folk who make up the resistance against #Gamergate. Check out my other interviews, with Leigh Alexander , Soha Kareem, Aevee Bee and Toni Rocca, Mattie Brice and Lana Polansky by clicking on the little purple words.

Here, I delve further into a conversation with games maker Christine Love and games writer Maddy Myers. You can read part 1, where we discuss femme at tech conferences and comforting loading sounds, here.

If you enjoy something, without trepidation, is it necessary to interrogate it? I guess now would be a good time to segway into Metroid—

Christine Love: Set aside the next hour.

I identify strongly as a Mommy/mother figure. For me, “mother” is an easier set of boxes to check than “woman.” Who the fuck knows what makes a woman? I don’t. I feel a lot of empathy for villains who are maternal, like Mother Brain, or Kamek from Yoshi’s Island, who uses magic to make the monsters grow and calls Yoshi a “cutie” a lot. I can understand “evil” through a maternal lens.

Maddy Myers: So Samus is a little of column A and Column B. I mean, I’ve read the manga, for better or worse. It’s not a very good manga, but it supposes that Samus has this relationship with Mother Brain and this relationship with the chozo, but also with the metroid that she meets. She’s in a way both a daughter, who has certain expectations of a daughter that she tries to live up to—and succeeds and fails depending—and she has expectations on herself to be kind of a mother figure to this metroid. For better or worse. This metroid is sort of struggling with its own identity as a metroid, which wants to suck people’s lives out, so there’s a lot of complexity there, which is why I like Metroid. I always feel like that’s something the people who’ve written for Metroid never know how to deal with. It’s why I like the Metroid games where there’s not so much talking, because I can then just put in what those characters are feeling, you know? I don’t have to listen to Samus talk, I can just be like “look, I got it.” I don’t know, I don’t like it when Samus talks.

Do you feel that Samus’ charge cannon fits Brianna Wu’s experience of femininity as “calculating”?

MM: Yeah, I think so, in the sense that Samus is constantly going back over old ground and finding new patterns there. I mean, that is a constant theme there—what makes the games feminine, intentionally or not, is that every game or nearly every game is about a homecoming. Samus is protecting her home, she’s going around these spaces that she’s visited before and collecting items and all of that is preparing. I guess you could say “manipulative” if you want to use a negative word that is frequently used to describe women or also "calculating," but it’s also like you’re being prepared; you’re noticing patterns, you’re getting ready to face the same enemies that you’ve fought before.

I think those things are coded as feminine, and introducing them into a game that is also about violence is interesting—and also part of what makes Metroid games stand apart a little bit from other “masculine-coded” space marine games. Like, Gears of War is a similar idea in the sense that you’re running around with a gun shooting aliens, but thematically and aesthetically and narratively, what happens in that game is completely different—you’re always exploring new ground, you never know what’s going to happen, and you can never be prepared. Marcus Fenix just has to fly by the seat of his pants. Metroid is just the opposite of that.

CL: Particularly in Metroid, notwithstanding the level design, there’s always the important thing of it always having to come full circle. You’re always coming back, in the end, to your home in the spaceship. In Metroid 2 you just walk back. There’s never this constant moving forward and then that’s it, that’s all over. You have to remember what you’re doing, you have to remember how the map works, because then you have to go back. It’s telling that the only time in a Metroid game where you have a time constraint is when you have to get back, in that final moment where everything’s about to blow up. Otherwise, you can take as much time as you want, you can go back and forth between these two rooms, figuring out what’s going on and then there’s a bonus in the end, but the game doesn’t tell you that beforehand, that’s just a surprise—

MM: Yes! But! The whole game is preparing you for that moment. Like, in the sense that you’re constantly going over old ground again and again. By the end of the game, you know the map so you’re ready for that moment when you have to escape in record time.

CL: Motherhood as a concept terrifies me, I don’t know if that’s something I’ll ever feel comfortable with—

MM: Yeah, same!

CL: But what I really like about Samus is that she’s also not comfortable with it. Like, just going off the games, you adopt a baby metroid after murdering its entire species and it guilts you into letting it follow you home, at which point you do a terrible job at tracking it. You are not a good mother and Samus is not a good mother at all. She doesn’t know how to do motherhood.

MM: Yeah, and she’s not that good as a daughter, either. I mean, Samus has a lot of problems, and that’s why I like her.

CL: I can engage with motherhood when it’s reluctant and “oh, it’s a baby making puppy dog eyes at me after I killed its species, all right, fine, I will reluctantly take care of you.”

I feel like “self vs. mother” is a common narrative trope in games.

CL: Can we talk about Navi? This is one of the most common memes from the Zelda series—Navi is hateable.

MM: Navi’s like your mom.

CL: She intrudes on the game world in a feminine voice, to tell you what to do. If you get lost, if you the player have been fucking up and don’t know what to do, if you are failing, Navi will help you, and people get so offended by this. This is such a huge slight.

Though that’s essentially what Cortana does for Master Chief.

MM: But Cortana is way sexier. Navi, I would say, is more like your mom in some ways because she keeps reminding you of your rules and your boundaries and that’s why there’s that tension there. This idea of a mom character being a villain is another weird pattern in games, for sure. Like that old WarioWare gamer level where there was the Mom character and she was evil—it’s very old, it doesn’t matter, some reader will remember it. Metroid has Mother Brain—

CL: Super Metroid is really mother vs. mother.

MM: I think that Navi is supposed to be your annoying mother, whereas Zelda is like the cool girlfriend that is unattainable. Zelda is the popular girl at school who won’t talk to you. So there are all these different tropes in games that line up with real nerd boy tropes. Even Link is the outcast made good, right? That’s very often how he’s framed. He’s just some weird kid who rises to prominence without the world and turns out to be a hero. That’s another thing that happens very often—and these feminine characters are sidelines to that.

What’s a smell that anchors you?

MM: Angers? Like makes me go “raaaahhhhhh”?

Anchors.

MM: Oh. Maybe like a pot roast. I had two parents who worked, so a lot of times I would let myself in after school and put that in, because it was so much easier. A lot of times I’d be home alone and there’d be a pot roast cooking and I’d be waiting, for hours, for my parents to come home. Just hanging out with pot roast—that’s kinda comforting. I never make pot roast now, because it seems really hard, but it’s probably not. I should probably do it.

CL: I cannot answer this question. I don’t have a very good sense of smell, actually—I mean it’s not that there’s nothing, just that people always talk about having really strong associations with smells and I’m just like “oh, well, I didn’t notice that at all.”

So, I have a separate question, and that can just be your question. How’s that?

MM: Yeah, do that. I’m not jealous. I’m definitely not jealous!

CL: I’ll take the vegetarian question option.

Disney has its own set of paints that you can go to Home Depot—it’s the specific shades that you find in their animated films. What is a specific shade of a color from a game that you think of often or resonates with you?

CL: Almost every game I’ve made has had blue growing screens, like the particular blue that a computer makes in the middle of the night, a very old one, like glowing in your face. That must be significant. That must mean something—it’s a very deep blue but it’s also just a little bit faded. I don’t know why that resonates so much. I don’t think I’ve really interrogated this too much and well, it’s calm, it’s not aggressive. It’s not bright, it’s just there.

What I like about femme expression—as opposed to just “being a feminine woman” is the variance and intent behind “overdoing it”—essentially the ability to build a genre out of yourself. What’s your genre of femme?

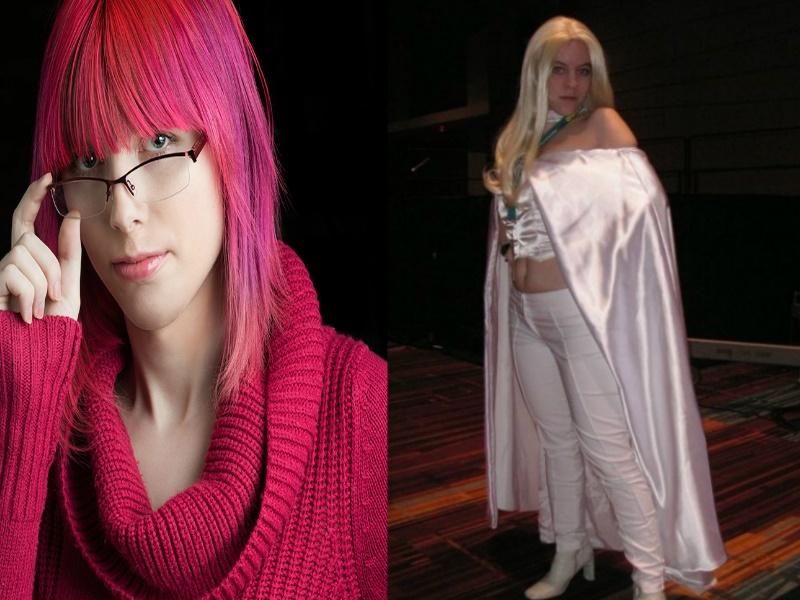

MM: It depends! One phrase that I invented for myself was “business goth” which is a type of femme in the sense that it’s a pencil skirt with other gothic signifiers. Like there are some Victorian elements, which goth usually has, but also some business elements like a tailored jacket, or a tie, but with other gothic elements like black lace. I do that when I’m going to work or if I’m trying to look professional, but Christine has met me so she knows I have some Lolita influences where I’ll wear petticoats or bloomers or opaque stockings and mary janes. That is the sort of style I do at conferences these days, because that’s the style that I’m more comfortable wearing, something fluffy. If sitting down a lot, you might as well bring your own pillow, right? Especially if you’re going to be sitting at a boring tech talk for four hours.

CL: It’s also the way you compensate for, you know, men always taking up space. Well fuck you, my giant-ass petticoat is going to take up space and you’re going to have to deal with that, and it’s going to be green and incredibly cute, but also you can’t get within two feet of me. Lolita fashion is a form of aggression. I feel very strongly about that. It’s rejecting sexualiation, it’s rejecting the male gaze. It’s taking up space, it’s being bold and it stands way the fuck out. It has this cutesy image but at the same time there is something incredibly aggressive about dressing Lolita.

MM: I think that’s in part because people don’t expect you to wear something that is coded as a child’s outfit. I wear plenty of things where people look and say “well, that’s very youthful” and I’m like “well screw you, because it’s not for you, it’s what I like.” I’ve tried to sort of describe it to people, and it might be tricky, but at least for me why I wear Lolita outfits is because it’s a hyper-feminine way of dressing that has nothing to do with sexuality, like Christine just said. But that’s also in part why it’s seen as childish, because we don’t see women as adults until they start dressing in a way that is “sexy,” according to our current definitions of sexy, blah blah society. Dressing like Lolita isn’t considered sexy and it’s not supposed to be, but a lot of people assume Lolita is supposed to be sexy. For me, it’s the opposite of that. It’s like what Princess Peach wears. I would dress like Princess Peach all the time if I could.

CL: People assume it’s supposed to be sexy but I don’t think anyone finds it sexy, and you know, that people are alienated by that, and frankly, I’m happy to alienate those people. If you’re uncomfortable with me wearing something unsexualized, great. Fuck you.

MM: Yeah! I completely agree. It’s also part of why I feel more comfortable wearing those outfits to conferences—I don’t want to be hit on there. So I wear something that is combatively saying “do not hit on me, do not sexualize me” by wearing a Lolita outfit with mary janes. Nobody’s going to hit on me in that, so now I can be a professional. It’s this ironic subversion of what I was trying to attempt for so long by wearing more masculine-coded clothing, and I’m achieving it by maxing out my femininity.

CL: I’ll say this, I’ve almost always gotten a positive reaction by dressing that way in conferences—even though paying attention to fashion is not valued, it’s not encouraged, people are still forced to engage with that, especially if it’s in a professional context. And the response is, when it’s not the “fuck you” response, often a certain amount of respect for being that bold. Which is actually pretty good for the conference—in a professional setting you want to be memorable. I feel like if these tech bros saw more of this, they wouldn’t have such hostile projections.

MM: It’s normalizing a woman being there by performing that, and performing the full extent of how I identify as femme. It should be normal to you, to see me dressed like this, and acting the way that I act.

What is a game—

MM: That’s the bigger question, isn’t it? What is a game? I don’t know!

—that embodies or is illustrative of non-sexualized femininity, to you?

MM: Metroid and Portal, to me, which are both—I think it’s sadly easy to come up with an answer to this because where we’re at a point in games right now where it’s men making stuff for men, and men have trouble knowing how to write a female character who isn’t a child if she’s the heroine or completely de-sexualized in some way, because they don’t know what it would look like if it were an adult woman who were sexual in a game. In some ways this is an easy question to answer because there are a lot of games about little girls who are completely chaste, or adult women who have absolutely no sexual identity that is seen in the game, like even the reboot of Tomb Raider—

CL: They’re “sexy” but not sexual—

MM: Yep! Yep! Yep! They can all share a dress size, let’s say. They all have the same measurements. Lara Croft doesn’t date anyone in the new Tomb Raider, and Remember Me has a heroine who isn’t presented as dating anyone and Samus doesn’t have a relationship—the one time that she does was so botched and so horribly that we’d all rather not think of it. It’s just not something I think men are able to write well. Even Tomb Raider had a lady writing it, and I think she’s talked in interviews about how she was discouraged against alienating the player, because these women are presented as chaste. But if you want an example of a good Lolita in a game, that I don’t know. Maybe Christine knows a good Lolita game.

CL: I can think of a lot of games that are about fashion but I don’t think the interaction with sexuality is there—fundamentally, games are terrified of women’s sexuality. That’s what it comes down to. It’s either a reward or something to be gazed at, but it’s never anything to sincerely engage with.

Does making female sexuality the reward effectively keep it out of the game? Is it a means of quarantine?

CL: I mean it certainly has that effect, for sure. I don’t know if the intent is quite so thoughtful, but if the end result is that the only time you ever engage with sexuality in a game is when basically either through the male gaze or otherwise, a male player is being rewarded with sexuality, then that makes a very specific impression.

At the end of my interviews, as surely you’ve read, I try to put the gaze back on myself, in a way, and interrogate my status as a “moderator” or “arbiter.” I want each of you to ask me an uncomfortable question.

MM: This is a question I’ve already answered in some of the things I’ve written so I’ll turn it back onto you—is there a game that you feel adequately represents your sexuality? Like you play it and you’re like “I can identify with a sexual relationship in this game." Does that game exist for you? It’s tough! There’s so few games out there—I’ve tried.

Portal.

MM: A-ha! The anti-sexual game!

At QGCon I was part of a lecture series about kinky sexuality in games. My talk, specifically, was about the intersections of game design and consent, specifically about pinball—but Lisa Yamasaki spoke about the sadomasochism of Portal (it’s the talk right after mine in the video). It was a really good talk, though I came away from it feeling as if the academic understanding of BDSM is like two decades behind actual lived experience.

The thing is: The reason why Portal resonates with me sexually is because I don’t see GLaDOS as the top. GLaDOS to me is sort of like AM in “I Have No Mouth And I Must Scream”—she is a bound intelligence, and so much of what she does, so much of her needling, of her antagonism of Chell comes from trying to negotiate this frustration of being omnipotent and all-powerful but still confined. Chell has the real power in that relationship. She has all the physical and emotional freedoms that GLaDOS is denied and without her, there is no testing, which is the one thing GLaDOS would say she lives for if in fact she were alive.

I enjoy torturing people—but I also wish I was the person being tortured, being beautiful. All of my partners are so beautiful. I wish I had their bodies, their compassion, their intelligence. Instead I tie them up, give them bruises and then we eat pound cake in bed and that gives me a sense of oneness or being intertwined with them in a holistic sense.

I mean, also my name’s DoubleCakes, so—

CL: So you relate to Portal but you don’t think GLaDOS is a domme. Have you had an experience in a game that does encapsulate your sadism?

At the same talk I just mentioned, some jokers thought they would try to get a rise out of me and Lisa by asking about consent in Portal—there’s two major impasses when you talk about consent in Portal. One, to what degree can an AI consent? Two, given that GLaDOS is an AI and we haven’t really established a rubric for sentience in AIs, how are we not sure that Chell hasn’t purposely gone through the “right motions” to get GLaDOS to try and hurt her? How do we know that GLaDOS isn’t just a jailbroken spanking machine?

We’ve gone from Peach to Metroid to Portal. This is the most casual game interview ever.

I would say the game that does relay my sadism would actually be Smash Bros. No one is ever damaged—people are hurt, and there are exclamations of being hurt, but everyone seems to enjoy it. Especially in the first one, in the Pokemon level, and you end up being hit by a Venusaur or a Voltorb, there is this moment where everyone is almost ecstatic. It’s like Team Rocket “blasting off again.” Team Rocket was always frustrated and chagrined but never in pain, and at the end of each episode they’re flying through the air, shouting—I think the enjoyment there is palpable.

MM: And it also takes place in a fan-fiction universe where none of these characters know each other except for the context of Smash, so it’s very playful for that reason, too.

There’s the video that introduces The Villager. He just shows up from behind Mario and puts him in a net and nobody’s in duress over this! Mario’s very amenable to that! That, to me, represents my relationship to sadism. It’s a compassionate distress.

Before we depart, tell me a little about your “femme arsenal.” What is something in your array of accessories that is central to the application of your identity? Let’s go out on some fashion advice!

CL: My glasses. They do nothing. They are totally fake. I have perfect vision—glasses are super important to me. This was when I started caring about my presentation. This is what really gave me the confidence. They’re something to hide behind that doesn’t actually hide you in any way whatsoever. It changes the way you look, and it gives you something to dramatically peer over, which is frankly, important for emoting. I always feel like this is the one thing that gives me confidence above all else. When I go without them, I feel naked, even though they give me no vision benefit whatsoever.

MM: For me, it’s almost always gonna be slips. I have one that’s particularly new, and I’ve started wearing it with everything. It’s like an element of an outfit that people don’t really see, because it’s just a little bit of lace peeking out and it’s just an accent, but it increases my self-confidence so much to have that extra layer. There’s probably some psychological thing, like it’s part of my armor, but I love slips, and I have so many. They’re my favorite article of clothing.

CL: Armor’s important.